The Biotech team at Gilmartin recently hosted a webinar with BTIG on Creative Financing and Investor Sentiment for Biotechs. The webinar featured a Q&A session that was joined by BTIG’s K.C. Stone (Managing Director, Head of Healthcare Investment Banking), Mikhail Keyserman (Managing Director, Healthcare Investment Banking) and Michael Karmiol (Managing Director & Head of Healthcare Equity Capital Markets). The webinar was moderated by Laurence Watts (Managing Director) and Stephen Jasper (Managing Director) of Gilmartin Group.

Here are our key takeaways from the Q&A discussion:

1. Biotech Valuations, Rebuilding Balance Sheets and Bankruptcies

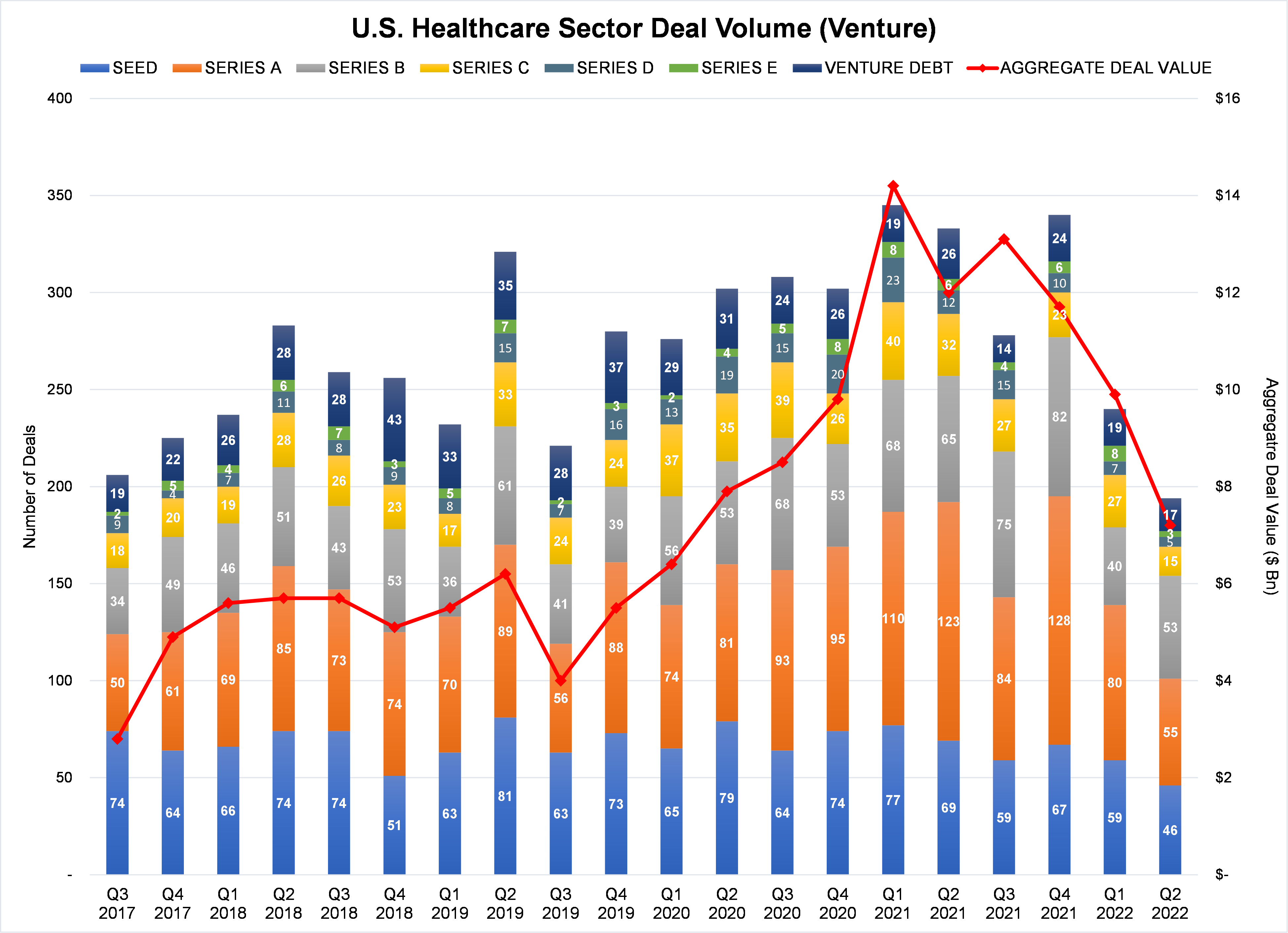

2022 has been a challenging year, particularly in the macro landscape. With around 200 companies trading at negative enterprise value, the capital markets have cooled off.

Costs of both clinical and pre-clinical studies have dramatically increased, resulting in a lot of companies exiting their clinical programs. As companies enter 2023, they need to streamline their focus on costs and rebuilding balance sheets while still being cautious of macro challenges. Bankruptcy continues to remain as the last option for biotechs even in the challenging market conditions. The ability to reduce burn without significant fixed expenses, quality programs, and valuable IP continues to play a vital role in avoiding bankruptcy in the biotech market.

2. Biotech Stock Price Recovery

Currently, investors continue to take a critical approach and emphasize selecting solid, de-risked stories with good management teams and science resulting in large caps and revenue generating companies to lead in 2023. As investors seek additional opportunities, the smaller caps will benefit, but the smaller micro-cap companies can expect to lag in the beginning of 2023.

3. Reopening of Capital Markets in 2023

Capital markets and M&A activity in the first quarter of 2022 was down 90% y/y, however the optimistic side of the story is that after the first quarter, equity capital markets in the healthcare sector have been up 50% each subsequent quarter. Building on the momentum, we can expect to enter a healthier M&A and capital markets in 2023 with maybe the small micro-cap companies lagging by a quarter.

4. Uptick in ATM Usage vs. Traditional Follow-Ons

The smaller cap companies can expect to start with ATMs as they have lacked the ability to finance using traditional methods. It is expected that biotechs with 3 key pillars (positive data, existing insider support, market cap) will continue to use more traditional financing and follow-ons. While ATM use is a great tool and good housekeeping for most biotechs, we will see a shift towards traditional financing and follow-ons as the capital markets start to improve, especially for the smaller-cap companies. Regardless of the type of financing, it is critical that biotechs get in front of the right institutional investors and build a syndicate.

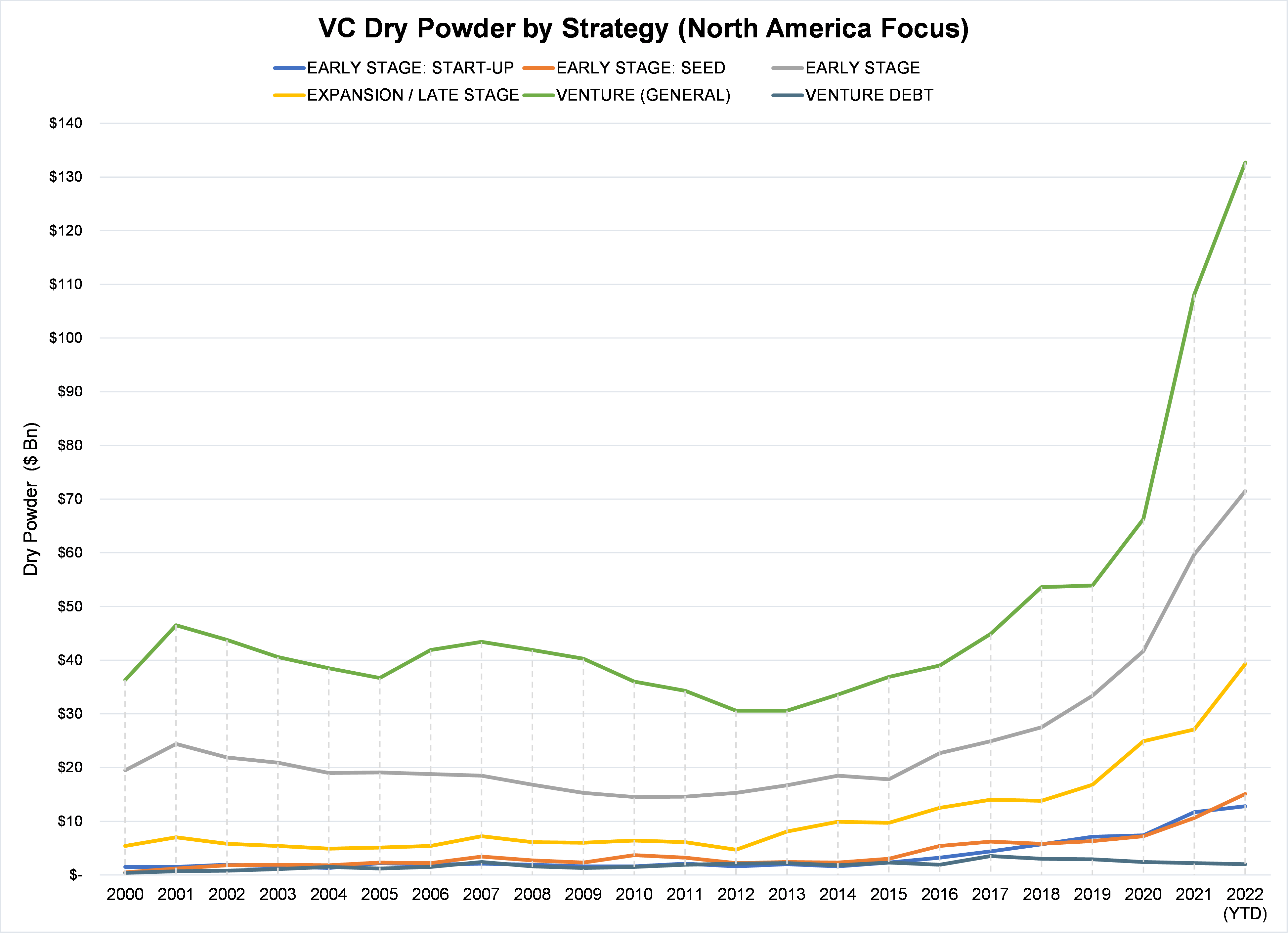

5. Current Financing Options for Biotech

Traditional financing options remain available for biotechs with data and market cap. In the absence of traditional financing options, alternative financing such as debt funds that weren’t previously made available in the healthcare sector have seen an uptick in the sector and continue to receive several opportunities. The market has also seen an uptick in IP monetization and royalty partnering.

6. Big Pharma M&A Activity

Anti-trust and FTC risks are currently on top of the minds of big pharma. Big pharma’s are mindful of therapeutic overlap and crowdedness. It is expected that in 2023, big pharma will look at complementary therapeutic areas and different types of assets instead of going bigger in areas they already have natural commercial and pipeline presence.

7. Healthcare Conferences & Investor Meetings

While investors are continuing to take meetings with companies they have pre-existing relationships with, they are slow to take new meetings. Incredible numbers of investors return to academic conferences to meet with KOLs and management teams. Having a comprehensive strategy for KOLs and helping investors get educated on a particular target and program is going to become more critical. Having thought leaders and objective KOLs presenting stories will be accretive to investors’ investment process and will lead them to do a lot more diligence work. Overall, especially in a difficult market, biotechs need to make their fundraising approach ongoing, and utilize healthcare conferences whether in person or virtual.

Gilmartin Group has deep experience working with both private and public companies in the Biotech sector. For more information about how we strategically partner with our clients, contact our team today.

Authored by: Rachna Udasi, Analyst, Gilmartin Group